Bastard Poems : Steel Incisors Press

£10.00 / 2 August 2021. 92 pages, full colour.

My selected collages, chosen from works made 2013 to 2021, and including an essay. Available here https://www.steelincisors.com/product/bastard-poems-by-sj-fowler/2

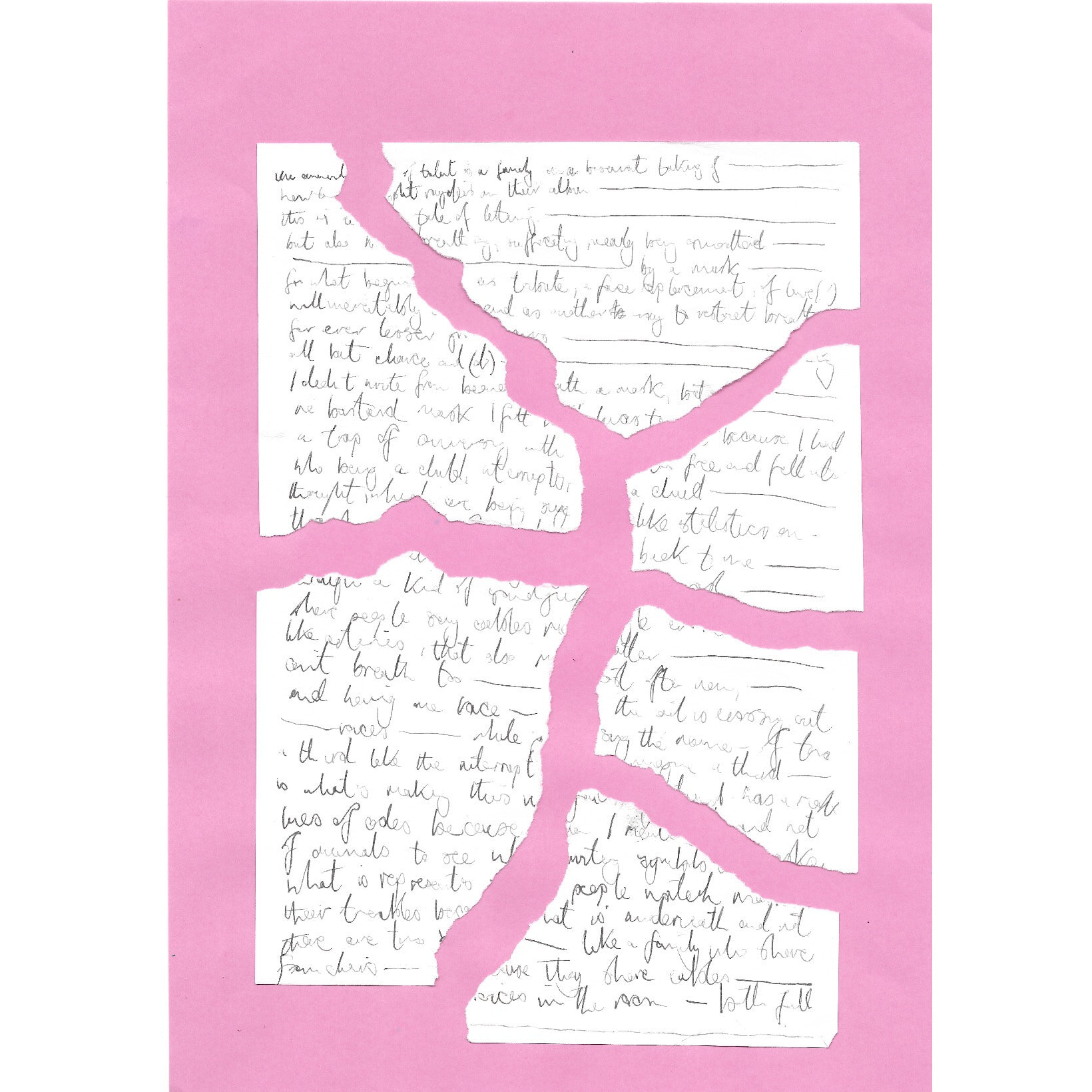

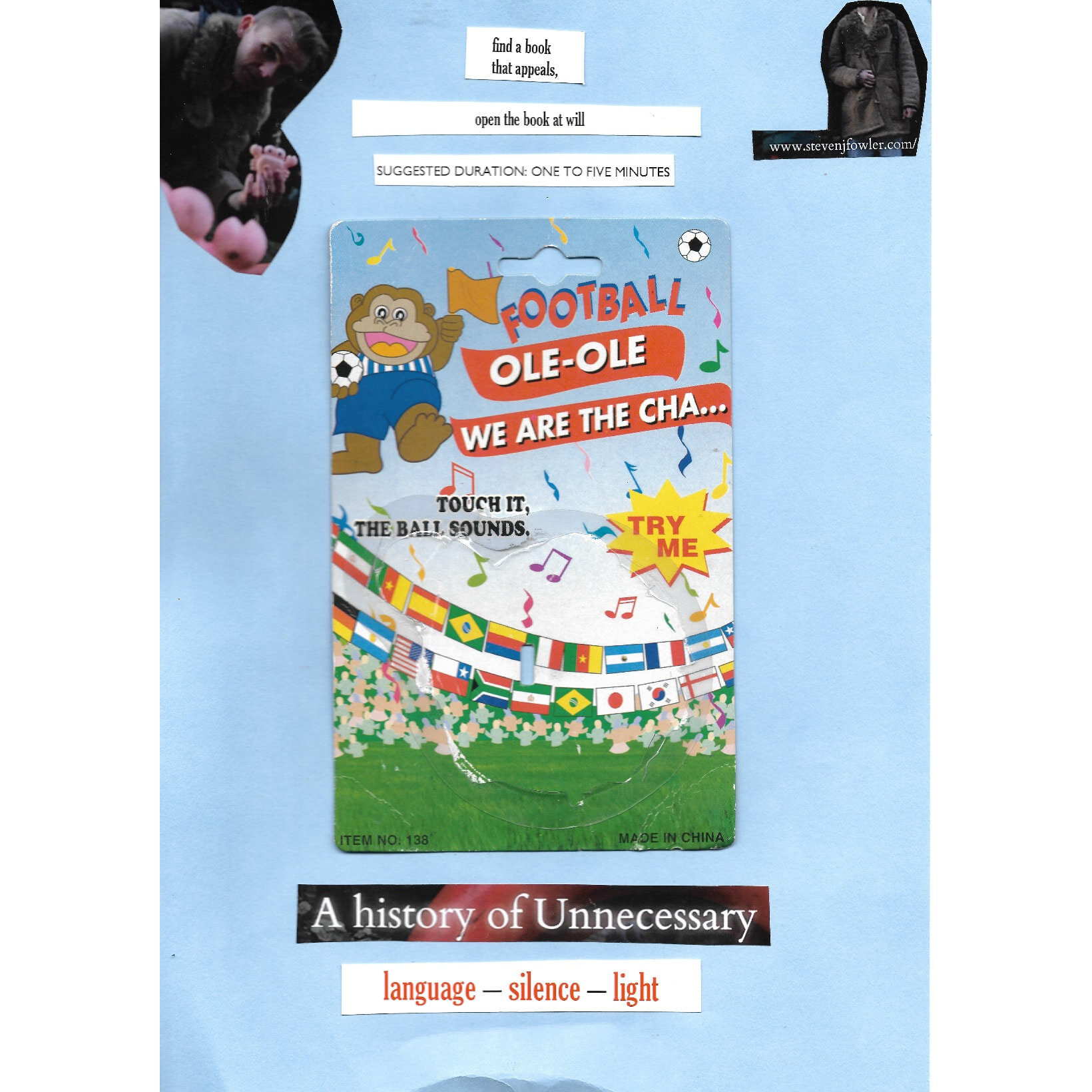

From the publisher “An unprecedented take on collage as poetic medium, SJ Fowler’s Bastard Poems is a book that defies description. Combining the found, the handwritten, the abstract, the irreverent and the archival, and the occasional text camouflaged as commentary, Fowler has devised a new form of poetry standing on the shoulders of a grand tradition. Here are labels and book pages, monkeys and footballers, self-help instructions and informational leaflets, plus lists, letters, tickets, drawings, maps, barcodes, birds, bears, and (!) more. Reading it is the equivalent of exploring someone’s abandoned attic only to realise they have been watching you the whole time.”

Here, and below, you can find an interview between editor James Knight and myself about the book https://www.steelincisors.com/s/stories/bastard-poems

Launch : Bath, UK on August 2nd 2021

With Angie Butler, Max Porter, Lucy English, Carrie Etter, James Knight, SJ Fowler and David Spittle. A brilliant evening of new experimental literary performance works, at the Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution, alongside readings of poetry and prose, celebrating the launch of SJ Fowler’s ‘Bastard Poems’ from Steel Incisors press

Samples from the book have been published online

Aww-Struck online exhibition and anthology : “Knut and Malthide’s Strawberry Jamm” https://www.poematlas.com/aww-struck

Beir Bua issue 2, page 8 : “Follo the Hollo” https://beirbuajournal.files.wordpress.com/2021/02/issue-2-15.pdf

Collage Poetry dot com : “Strange Latin Yacht” http://collagepoetry.com/strange-latin-yacht-steven-j-fowler-uk/ and “Infinite Italian Snowfall” http://collagepoetry.com/infinite-italian-snowfall-steven-j-fowler-uk/

Extract from review of Bastard Poems from Mark Wynne on Steel Incisors - 07/08/21

https://steelincisorsvispo.wordpress.com/2021/08/07/bastard-poems-a-review-by-mark-wynne

Interview with James Knight, about Bastard Poems - 01/08/21

JK - Poets and artists habitually stress the value, significance and beauty of their work. “Bastard Poems” suggests the opposite. What was your thinking behind the title?

SJF - The title comes from seeking an alternative to Collage Poems, which was the working title. I am cautiously pleased of my book titles, usually, and I spend a lot of time working on them, trying lots of ideas and variations for each book. I feel if the content of a poetry collection is as mine are, then the title and cover better be good.

I felt Collage Poems was accurate, and would line up with my Crayon Poems and Sticker Poems collections, as a kind of series, but it wasn't truly representative of what I'm doing in the book. The works are Collages, strictly speaking, but they also use archival material, technique layering, with handwriting, asemic writing and printed texts too, added with a phone app. So they aren't what people think of as classic Collage.

Bastard is also a good word I think. One of the better English curses, which is relatively inoffensive nowadays, though it may shift. It's there with gobshite and shitehawk and git and others I won't dare name. I think Bastard is divorced somewhat from its meaning around illegitimate birth, meaning an unpleasant person in most people's minds instead. But I intend it to refer to its adjective form

adjective

1.

(of a thing) no longer in its pure or original form; debased.

"a bastard Darwinism"

I like how google chooses Darwinism as the example! But this is what the book is, poems no longer in their pure or original form, found, made, scrapped, discovered, re-used. And to your first point, I think the irony is I do believe in an objective standard of beauty, and an objective gradation of quality in poetry and art, so I have some sympathy for those who stress those qualities in their work. I just think I think the criteria on which both of these things are based is a touch different than many who define those terms in the general consciousness of England in the 21st century. The title emerges from this perhaps, from a sense that humour, flippancy, irony, authenticity are quite compatible with me thinking my work is beautiful.

Though I don't think my work is particularly valuable or significant, you are entirely correct there.

JK - Can you tell me more about the role humour plays in your work?

SJF - I think anyone who says they write funny poetry is suspect. But a kind of humour is almost always in my work. It's absurd just being a poet. And this is what I do, what I've ended up doing with my life, and so I'm pleased if my poems to contain a trace of that ridiculousness. They can do that, I think, and be more affective, more meaningful, because they are self-aware about their possible stupidity. Which is an extension of what I aim to be as a person. I am writing little chunks of weird language that almost no one reads, as a profession. In this book, I am sticking stuff together I find interesting and amusing and meaningful. This is quite funny. I often actively seek weird and outlandish language or language worlds or materials because that's what I find pleasing or exciting or insightful. Then I often place things together that are amusing because of their obscure difference.

The reality for me is that I've spent most of my childhood and worklife with groups of people making jokes to show affection, undercutting the absurdity of situations, collectively. Now I'm mostly working alone, making stuff, and the absence of that collective humour makes it into my poems instead.

If I was being theoretical I'd say Freud's later theories on humour are relevant. In his 1927 writings, Freud shows how the phenomenon of humour is the contribution made to the comic by the super-ego. In humour, the super-ego observes the ego from an inflated position, which makes the ego itself look tiny and trivial. The core insight is that in humour we find ourselves ludicrous and we acknowledge this in laughter. Humour is essentially self-mocking derision, and all Freudian humour is replete with unhappy black bile, melancholia. The humour here is not depressing but rather liberating and elevating. Here is the world, which seems so perilous but it's a nothing but a joke. There is no final answer, no perfect moment, no satisfying turn. How much sillier could it be that we are sentient apes who know we are alive and know we will die and are able to perceive enough to know we don't know much and must strive for meaning anyway. And then I am in that, sticking together pieces of paper with pritt stick and sending it to you James!

JK - Your comments about the darkness at the heart of humour and your fascination with placing things together “that are amusing because of their obscure difference” immediately brought to mind André Breton’s writings about black humour and the surrealist image as a union of two more or less distant realities. It also strikes me that much of your work enacts a gleefully ludic subversion of cultural values and aesthetics, close in spirit (if not in style) to Surrealism. Would you say that consciously or unconsciously you have been influenced by the Surrealist movement?

SJF - Unconsciously, noting the irony, and second hand. I am interested in psychoanalysis, but it doesn't directly appear in my works. I've spent time reading Otto Rank concentratedly, and I like Anthony Storr a lot. But I am very suspicious of it, as an enterprise. I think it's quite close to what poetry should be sometimes, specious and linguistic and ludic. Useful complex metaphors one shouldn't take too seriously. Language games that illuminate. Continental theory even more so! It's poetry. It is often full of random, specious conceptual leaps of faith and non-sequiturs all rooted in language. The world should maintain its suspicions of those who wish to be psychoanalysts, or theorists, as they are poets with a wish for power.

But to stick to the point, that concern with the unknown, unknowable, I share with Surrealism. Their passion for those lived elements of psychoanalysis, sex, the death drive, the mind, repression, perversion. That's really what I'm also interested in. But I never read them properly, or early on, so I reckon I took their influence from poets like Gunnar Ekelof, Henri Michaux, Karel Appel and Tomaz Salamun, who were likely influenced by Breton et al.

I do teach Surrealism every year too, so I keep meaning to go deeper, to understand more about them, as you do, as my friend David Spittle does, but they don't connect with me somehow. They are too confident maybe? But figures like Mallarme and Apollinaire, and the Dadaists, I feel it more. I've often said one of my biggest influences is Chris Morris, the British satirist, and the band Ween. Could they exist without Surrealism? I think so, yes, but still, some connection there.

JK - You mentioned having a small readership. However, you have tirelessly promoted and galvanised the avant-garde, and have done much to bring attention to writers and artists who are part of that scene. Do you think the audience is growing, or could grow?

SJF – In a nice way, I'd say not really and probably not. I am however definitely sure I'm not sure I want the audience to grow. If the work is by its nature complex, it won't appeal to large swathes of people, most of the time, with occasional exceptions (in the past, it seems, in poetry). So if the audience grows significantly I would wonder why? Of course there are other factors. The fact is that poetry isn't necessarily good for us, as writers or readers. And we have to find our own way to it, to gain from it, to give it the proper attention. It is a niche for a reason, and we, experimenting, looking into the future, considering existence as combative and preposterous, and making work in that vein, acknowledging our inability to be 'insightful' given the nature of language and living itself, are not going to be popular. That's probably as it should be? At best, we are going to have deep responses in small numbers. While that which pleases, or comforts (in content or style), or is temporarily fashionable, or generalised, or contextually beneficial to the reader by association, will be very popular. I hope I am self-aware enough to say I don't believe this to buoy myself, it just seems logical.

But then I'd say a lot of what I do isn't that experimental, or certainly skirts around it. I want to be able to do what I want basically, however that comes out. And sometimes we have to be aware the avant garde is a term used by people who wish to look cool and radical when they are not willing to find out if they actually are interested in interesting ideas. There is no virtue in obscurity. It's just a by product.

JK - You seem to favour physical materials and processes over digital means of expression. Is that a fair comment, and if so what is it that draws you to scraps of paper and pritt-stick?

SJF - It's absolutely true yes. I've nothing actively against the digital in terms of creative possibility and material but I've found deep personal satisfaction, spending so much time working in that realm for other means, to have the visual workings I do, which are done in a studio, surrounded by things, to be actively tactile. I want there to be sensory processes, and that they lead the way in fact. I want to return to that feel because of the internet. If collage was the greatest artistic revolution of the 20th century, according to Gregory Ulmer, and I am here making Bastard poems as a kind of collected Collages, which it is, then I want them to be as physical, clumsy, ugly, weird, papery, child-like and messy as possible. The materials themselves are the point I would say, to create the chance and juxtaposition in their coming together that surprise me and make the work.

That said, there is a digital element to Bastard Poems. I have taken some works and used a phone app to write bursts of poetry upon them, almost commentaries, where I feel it is needed, lest the book become repetitive in its material density, and when I wanted to. The aberrant poems, typed in this one single app, have elevated the book I think, because they add a semantic density, and lightness, which makes the images vie as illustrations with and of the text.

JK - You mentioned your admiration for Dada and “provocative immaturity”. I think there’s room for much more of the latter in today’s poetry scene. Of your many works, which do you think best exemplify this bracing spirt of anarchic puerility?

SJF - I agree with you, but I think the price to pay for most is too high now, it's a lot of risk. I sometimes teach the Viennese Aktionists, and the Wienne Gruppe, and Peter Handke, Jelinek, Bernhard and I think of what they did and why they did it, and it helps me understand the change. They were railing against complicity in WWII, as Dada was made of WWI. Whereas when I smashed a building with a spade during a performance in Latvia, sent by the British Council, I was just annoying people. I think most of my books have semi-regular provocations, and many of my performances too. There was a period of maybe 3 years when I was getting experience performing but was still embarrassed to do so, feeling my roots in environments without public creative expressions, and was using my martial arts and physicality to get through that self-awareness. In that time I was falling into the trap of enjoying winding people up and being confrontational because I was insecure. I knew this as I was doing it, and I'm not declaiming it. The EVP tour in 2013, I was sick on stage, pretended to cut my throat, had a mock fight with bouncers. Stuff like that. I wouldn't do it now. Instead, now, I'd rather let the provocation be awkward, appear accidental, make things more subtle. It's just an evolution of experience and interest. Books like Bastard Poems are somehow provocations too, but not by design. I suppose this all depends on the audience or reader's perspective and tolerance.

JK - Your comment about people’s adoption of the label “avant-garde” struck a chord with me. It strikes me that there is a danger that people locate themselves lazily within what is, after all, a tradition like any other, and adhere dogmatically to a set of precepts laid down by others decades ago. As I said in a recent tweet, I love the avant-garde’s risk-taking and sense of adventure (read, FUN), but I’ve no time for the prohibitions and sneering. That said, labels can be useful in grouping artists together, giving them a sense of shared experience, and making it easier, perhaps, for new audiences to find out about them. A good example is the Young British Artists of the 1990s, a disparate bunch, who profited in more ways than one from the YBA label. Do you think such labels still have value? Can we turn them to our advantage, without seeming pompous or blinkered?

SJF – I think so much of this is about who makes the labels and how they stick. If you and I and the hundreds of other brilliant 'avant garde' poets in the UK (there are more, but at least this number of published, established, present poets in the various traditions of experimentation) were suddenly put within a label, the new vanguard, the bird king group, fowler's pickles etc… and conferences, then books, and newspaper articles were written about it, then we'd all get more exposure. Then we'd become satisfied and reject it. I was never in the bird king group, critics lumped me into that. I think so much of what I've been interested in has overlapped with specific elements of the avant garde because they were future facing and had an understanding of literature that was complex. But loads of it means nothing to me, and increasingly I'd like to call myself an eccentric poet, or weird, but then that word doesn't work. There is something anonymous and disparate about us without a label, and if we can let our egos appreciate that for the greatness it is, then being in the shadows is a small price to pay when you see what is in the light.

The avant garde almost means nothing, just like the word mainstream is ridiculous. But then without these terms, how could we situate ourselves? With longer descriptors. And there is an irony about language artists using poorly realised terms which is quite enjoyable too.